Subgenus Astropolium in Symphyotrichum contains our Saltmarsh asters, as they are called. They're pretty easy to recognize: reduced, narrow stem leaves around the flowers that are pressed against the stem; glabrous or nearly glabrous stems and leaves; a dispersed out, paniculate arrangement of flowers. Currently three species seem to be recognized:

- Perennial Saltmarsh Aster, Symphyotrichum tenuifolium

- Southwestern Annual Saltmarsh Aster, Symphyotrichum expansum

- Annual Saltmarsh Aster, Symphyotrichum subulatum

- Southern Annual Saltmarsh Aster, Symphyotrichum divaricatum

These last two are the ones I am focusing on (though I will briefly go over the 2nd species). I feel like there is a bit a confusion regarding these two species—likely due to their taxonomic history—and want to clear that up a bit.

Too Long, Didn't Read?

In a nutshell: While Symphyotrichum divaricatum is widespread throughout Texas on a variety of habitats, Symphyotrichum subulatum only occurs in the far southeast corner of the state and only in saline locations—salt marshes, tidal flats, and sometimes along salted highways. This means that unless you have a plant in one of those habitats, I'd argue it's almost guaranteed that your Saltmarsh aster is Symphyotrichum divaricatum and not S. subulatum, particularly if it's growing in a weedy lawn or disturbed area.

There are ways to distinguish the two morphologically through flower arrangement and phyllary details, but in my opinion, location and habitat should be suitable for IDing S. divaricatum for the vast majority of observations in Texas. Where things may be more difficult are places where a third species, S. expansum, occurs alongside S. divaricatum because of overlap in range, ecological niche, and intermediate individuals (appearing to be a mix of both) - this overlap is mostly restricted in West Texas (see BONAP map, which appears accurate for this species). I ultimately leave it up to the iNaturalist community to decide how to tackle these observations.

Brief Taxonomic Background

In short, Symphyotrichum divaricatum was once considered a variety of Symphyotrichum subulatum, known as Symphyotrichum subulatum var. ligulatum, and is treated as such in Flora of North America and many older publications. However, recent work by Guy L. Nesom (2005) split the varieties into their own species, and this has largely been accepted by the botanical community, as can be seen the draft treatment for the East Texas Asteraceae for the in-production Flora of East Texas.

The reasons for this are explained clearly in the Flora of North America discussion under S. subulatum:

- The geographic range of the varieties barely overlap—"nearly allopatric" is the term used.

- The varieties are "mostly reproductively isolated:" while intermediates (individuals with characteristics in-between both varieties) occur in areas where varieties overlap, experiments by S. D. Sundberg (1986) found that hybrid individuals are mostly sterile and unable to produce viable offspring.

- Differences in morphology and ecology.

S. subulatum, S. divaricatum, and S. expansum are the three species occurring in Texas resulting from this taxonomic change:

-

Symphyotrichum subulatum var. ligulatum, >>> Symphyotrichum divaricatum - Southern annual saltmarsh aster

-

Symphyotrichum subulatum var. subulatum, >>> Symphyotrichum subulatum - Annual saltmarsh aster

-

Symphyotrichum subulatum var. parviflorum >>> Symphyotrichum expansum - Southwestern annual saltmarsh aster

Such differences will become clear soon when I go over these two species.

Geographic and Ecological Isolation

The range of S. divaricatum and S. subulatum overlap... but barely. To bring this point, go to the East Texas Asteraceae draft, and then find the county-level maps for both species (page 189 & 191). If you do, you will find the following:

- S. divaricatum: Widespread through all of Texas.

- S. subulatum: In 4 counties on the far southeast corner of the state.

The third former S. subulatum variety, S. expansum, overlaps slightly with S. divaricatum in West Texas. Putative intermediates have been found in that overlap region.

The two species are well-separated ecologically as well. In the East Texas Asteraceae draft, S. subulatum is "restricted to salt marshes and tidal flats of the Gulf Coast." S. divaricatum on the other hand is less picky, growing in moist areas, disturbed sites, and often weedy lawns—but does not grow in saturated, salty locations. Thus, if one finds a Saltmarsh Aster in a weedy lawn it is almost certainly S. divaricatum and not S. subulatum.

Left shows S. divaricatum in disturbed, weedy area. Right shows S. subulatum in saltmarsh habitat. Images from https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/195684456 and https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/16450259

S. divaricatum in low-cut lawn. This species tolerates mowing well, even adjusting to flower at the mow line! Image from https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/98241703

Flora of North America notes that S. subulatum (treated at variety level) has been known to occur inland in "salted habitats" around the Great Lakes, listing "brackish marshes" and "salted highways" among possible habitat. It is possible that seeds of S. subulatum from the coast could be deposited deeper inland in Texas given in lands in suitable saline habitat, similar to occurrences in Michigan or Ohio—something to keep in mind.

Differentiation of Species Morphologically

In the Flora of East Texas draft, the two species are distinguished morphologically in two different ways: the arrangement of the flowers (inflorescence structure) and the phyllaries.

Symphyotrichum subulatum has its heads arranged in a dense, pyramidal array, with flowers grouped close together:

See more specimens images here.

I would say that "dense" is a relative term here: the flowers are still spread out, and on the lower branches of the pyramid are further spaced apart. The inflorescence is most dense towards the top of the pyramid.

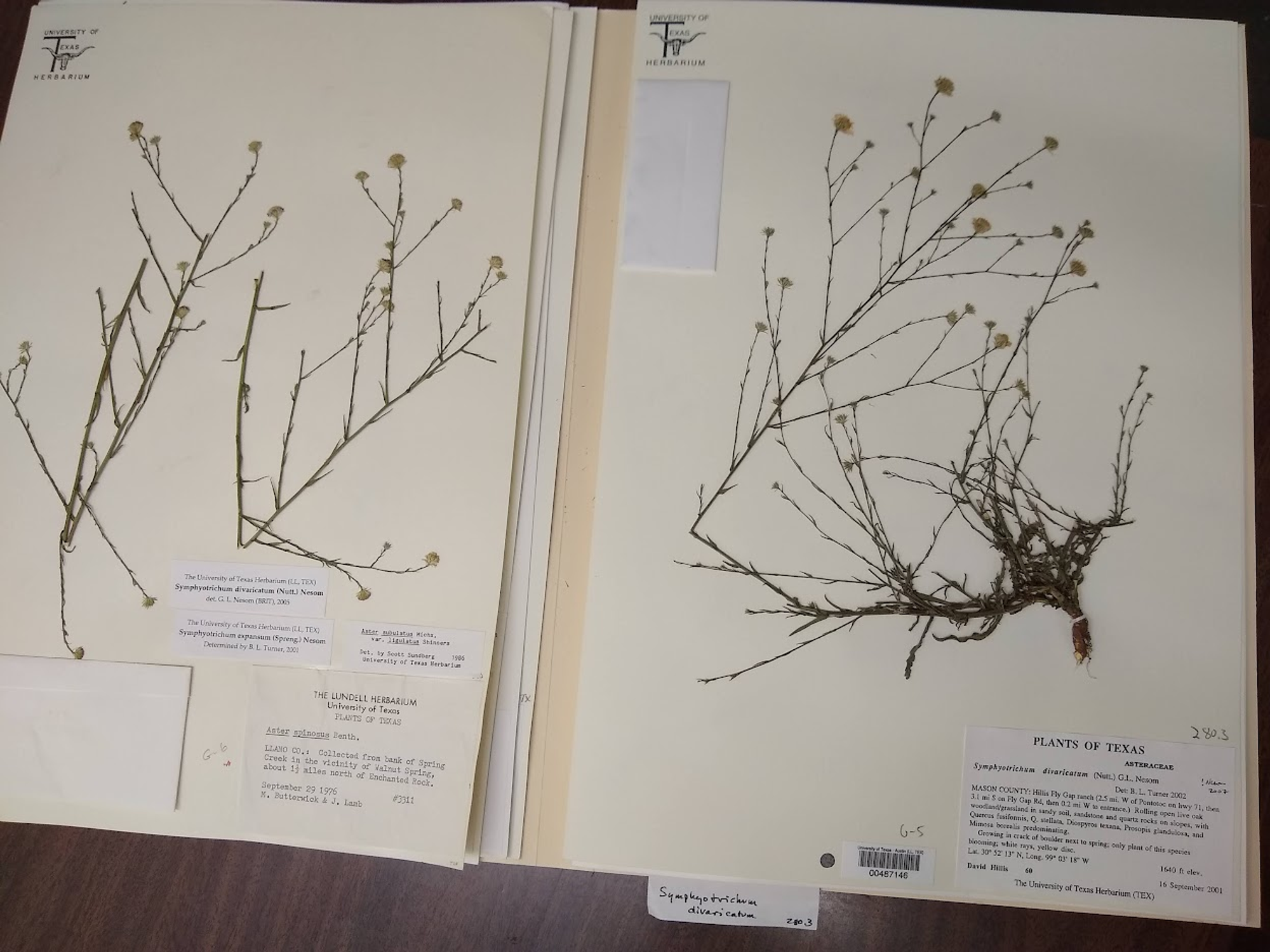

"Dense" is thus relative to Symphyotrichum divaricatum, which has its heads in a very diffuse, open arrangement. Notice the vast amounts of negative space between the flowers compared to the previous species:

See more specimen images here.

At its most crazy, S. divaricatum flowers can be so spread out that they almost seem to float in midair.

Of course, if the plants get cut or mowed back the flowering arrangement will look different (maybe even doing the "flower from the mow-line" party trick). But as previously mentioned, any plant in a disturbed or weedy area in Texas is almost certainly going to be S. divaricatum.

I will note that the inflorescence arrangement can be variable and might be ambiguous on occasions.

The other method, using phyllaries, is confounding to me and I have been unable to see it reliably. The first part refers to the green zone on the phyllaries. On S. divaricatum (left image) the green zone extends the entire length of the phyllaries; on S. subulatum (right image) the green zone is restricted to the upper portion.

These were the two most clear-cut examples I could find, from observations that I carefully assessed were ID'd correctly. In most other observations and pressed specimens, it was incredibly difficult to see any real difference at all. Images from https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/98435941 and https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/138267257

Then there is the note on "hardened bases." As of me writing this (January 2023) I have yet to figure out what exactly this means. What is hardened about the phyllaries on S. divaricatum? What does it mean if the phyllaries are not hardened like in S. subulatum? Maybe a more thorough review of the literature will yield more information on this, but until then I remain confounded on how to use this character.

Conclusion

The ultimate purpose of this journal post is mainly to clarify the situation between Symphyotrichum divaricatum and S. subulatum, which seem to cause a lot of confusion at least in Texas. My personal opinion is that the vast majority of Saltmarsh asters observations in Texas can be accurately identified as Symphyotrichum divaricatum based on location and habitat; after all, throughout most of Texas it is virtually the only Saltmarsh aster species present.

I do feel that for S. subulatum, habitat alone may not enough, because its range overlaps with S. divaricatum (even if they are said to occupy different ecological niches); for a species ID I would suggest at least a photo showing the pyramidal inflorescence structure to help confirm the identity of the plant. Certain plants would likely require more scrutinization for ID,

There is the possibility of mistakingly marking S. subulatum as S. divaricatum for individuals that sneak further inland in suitable habitat e.g. saline marsh areas, salted highway roadsides and ditches. However, the current situation with Saltmarsh asters in Texas is likely not better, just due to general lack of knowledge along with the close similarity between these species.

I have also neglected to look in-depth at Symphyotrichum expansum. Things may be more difficult where Symphyotrichum expansum occurs alongside S. divaricatum due to overlap in range, ecological niche, and intermediate individuals (plants appearing to be a mix of both). This overlap is mostly restricted in West Texas (see BONAP map, which appears quite accurate for this species).

While I have made my position regarding these plants clear in the previous paragraphs, I ultimately leave it up to the iNaturalist community to decide how to tackle these observations. And for those seeking a better understanding of these two species and how to photograph and identify them—I hope this is informative and useful to you.

Consulted Literature

Brouillet, L. et al. Symphyotrichum subg. *Astropolium. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 25+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 20. http://floranorthamerica.org/Symphyotrichum_subg._Astropolium.

Brouillet, L. et al. Symphyotrichum subulatum. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 25+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 20. http://floranorthamerica.org/Symphyotrichum_subulatum.

Brouillet, L. et al. Symphyotrichum subulatum var. subulatum. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 25+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 20. http://floranorthamerica.org/Symphyotrichum_subulatum_var_subulatum.

Brouillet, L. et al. Symphyotrichum subulatum var. ligulatum. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 25+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 20. http://floranorthamerica.org/Symphyotrichum_subulatum_var_ligulatum.

Carr, W. R. (2008+). Travis County Flora Project. Archived version: http://web.archive.org/web/20220404171225/https://npsot.org/Austin/TravisCountyFlora/Travis%20County%20Flora.html

Neill A. K., contributor (2019). Asteraceae of East Texas. For Diggs et al. Illustrated Flora of East Texas series. Botanical Research Institute of Texas Press. https://fwbg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Asteraceae_East_Texas_download.pdf.

Nesom, G. L. (2005). TAXONOMY OF THE SYMPHYOTRICHUM (ASTER) SUBULATUM GROUP AND SYMPHYOTRICHUM (ASTER) TENUIFOLIUM (ASTERACEAE: ASTEREAE). SIDA, Contributions to Botany, 21(4), 2125–2140. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41968509

Sundberg, S. D. (2004). NEW COMBINATIONS IN NORTH AMERICAN SYMPHYOTRICHUM SUBGENUS ASTROPOLIUM (ASTERACEAE: ASTEREAE). SIDA, Contributions to Botany, 21(2), 903–910. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41968346